How does a poem differ from ordinary prose? Poems with rhyming lines and obvious rhythm are easy to recognise, but words can still be a poem without these elements.

For me, it is in the moulding of the words. A poem that has had work done to it – like a lump of clay that is roughly formed into the shape of a vase and then painstakingly worked on until it is perfect, lovingly fired and adorned with colour.

I recommend you visit the websites below to read different types of poems and to also hear them being read aloud (Poetry Foundation). Poems are designed to be heard – they often make more sense when they are read aloud; indeed, learning how to read poetry is a skill in itself and if you get a chance to go to an ‘open mic poetry night’, you will probably hear the marked difference between poets who simply read their poems out loud and those who ‘perform’ them.

www.poetryfoundation.org/learn

www.writersdigest.com/whats-new/list-of-50-poetic-forms-for-poets

The (optional) ingredients of a poem

A message or a story

A poem often has a message; be it political, personal or satirical. Or it can be a story, a moral, or an observation.

Two examples of poems that tell stories are Annabel Lee by Edgar Allan Poe and Madeline by Ludwig Bemelmans

Lots of poems for children contain morals. A slightly gruesome example is Matilda by Hilaire Belloc which explains the importance of telling the truth.

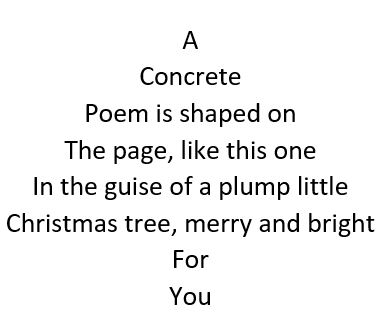

Form or structure

Poems often have a form; a set structure, such as rhyming pairs of lines, or a specific rhyme scheme, a pattern of repeating lines, a set number of syllables per line and a specific line count for each stanza (verse). Sometimes they have an actual physical shape (a concrete poem), like a Christmas tree, or anything really.

Quick reminder:

A syllable is a part of a word that has a single vowel sound and is said as a single unit – for example, TREE has only one syllable, FALLING has two FALL-ING, INTERNAL has three IN-TER-NAL and INSTITUTIONAL has five IN-STI-TU-TION-AL.

Rhyme scheme (or none)

Many popular poems rhyme, but the taste for rhyming comes and goes and currently, it is out of fashion (which is a shame, because I love to rhyme!). However, the reason many poems remain popular is because of their memorable and pleasing rhymes.

Rhythm

Like a song with a defining drum beat, many poems have a rhythm that is intentionally set by writer. The most well-known of these is the IAMBIC PENTAMETER, used by Shakespeare; which is the use of alternating stressed and unstressed syllables that make the poem lines read with a ‘da-dum, da-dum, da-um, da-dum, da-dum beat.

This the first (and probably, most famous) line from William Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18, showing the stressed syllables in bold:

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Style

The style, or ‘voice’ of a poem will often match the subject – unusual ‘turns of phrase’ can be used, as well as made-up words strange pronunciations and all sorts. You can really mess around with language in a poem.

Punctuation and Line breaks

In a poem, a sentence can be broken up into several lines – even mid-sentence to make it fit the ‘form’ or chosen rhyme-scheme. A line break can also work as punctuation, because the reader will naturally pause at the end of a line (unless you direct them not to, when it is performed).

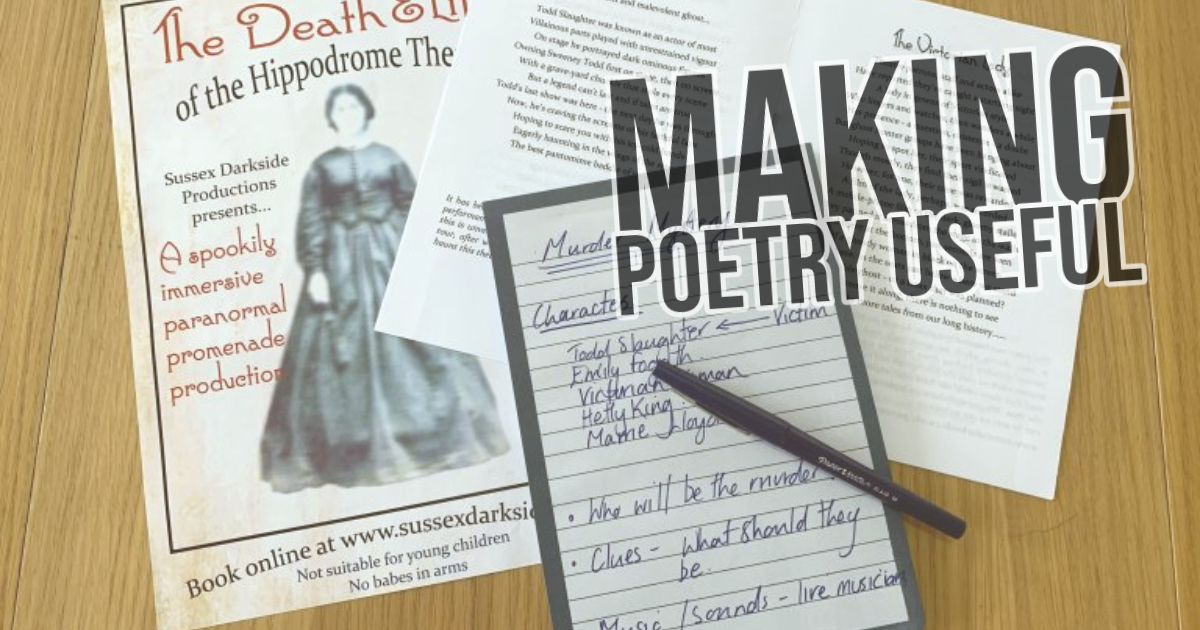

For example, in this poem extract from my production, The Death and Life of the Hippodrome, one sentence is broken into four lines, to force it to fit the eleven syllables per-line form that I chose:

It was commonly known that sailors in need

Of earning some money, were sure to succeed

To gain a small income from pulling the ropes

At local playhouses, not far from their boats

However, when this poem is performed, it is read as one sentence:

It was commonly known that sailors in need of earning some money were sure to succeed, to gain a small income from pulling the ropes at local playhouses, not far from their boats.

Some poems have punctuation (commas, full-stops, etc…), some have none. In modern poetry, either is fine. The key is to ensure the reader understands how to read the poem through the writer’s use of either line-breaks, punctuation, or a combination of both

Or none

A poem may have none of the above ingredients.

Free verse has little to differentiate itself from prose – however, it is the intention of the writer and the work done to the words that define it as a poem (in my personal opinion), although not everyone is a fan, or would agree with this!

Poetic forms

There are all sorts of rhyme schemes used in poetry and these are denoted by letter patterns, showing which lines rhyme with which, for example: alternate rhyming lines are an ABAB rhyme scheme, like in this extract from my poem called Pelt:

A fox of notoriety (A)

A tail of thick and fiery fur (B)

Producer of strong progeny (A)

Sly master of the bin procure (B)

Rhyming couplets (pairs of rhyming lines) are AA, BB, CC and so on, seen here in my poem, Night.

Day turns to night and then night slinks away (A)

Overawed by her aura, embarrassed to stay (A)

She reproaches his tricks and his childish pranks (B)

And the nightmare conspirators caught in his ranks (B)

The streetlights abetting his fingering shadows (C)

The devious rustlings of ravenous hedgerows (C)

Mix these patterns with FORM and set SYLLABLE COUNTS and other rules, and poetry can become quite complex (but extremely fun) to write!

There are lots of poetic forms, but here are some popular ones

Quick reminder:

A stanza is a set or group of lines in a poem with a set form. A verse is pretty much the same thing but refers to a group of lines in a poem without a set form.

Acrostic: This is a very popular form for children to write because the only rule is that when you read the first letter of each line in the poem, going downwards, it will spell out a word or a message. Obviously, you need to choose the word or message before you write the poem.

Triplet: Uses rhyme scheme in sets of AAA.

Monorhyme: Is a poem in which every line ends with the same rhyme sound.

Enclosed rhyme: Uses rhyme scheme of ABBA for the four lines of each stanza. Which means that the first and fourth lines rhyme, and the two middle lines rhyme.

Terza rima: Uses an unlimited number of stanzas of three lines each (called tercets) and has rhyme pattern of ABA BCB CDC DED, which means that the middle line of each stanza becomes the first and third line rhymes for the next stanza. A Terza rima usually ends with either a single line, or a rhyming couplet using the same rhyme sound as the middle line from the previous (last) stanza or tercet.

Limerick: Is usually a humorous (and sometimes rude) poem, quite often poking fun at someone or something. It is only five lines long and has a rhyme scheme of AABBA.

Villanelle: A nineteen-line poem consisting of five tercets (stanzas of three lines each) and a final quatrain (four line stanza).

It uses a rhyme scheme of A1bA2, abA1, abA2, abA1, abA2, abA1A2. The number denotes a repeating line, in that line one (A1) is repeated in line six, twelve and eighteen, then line three (A2) is also repeated at lines nine, fifteen and nineteen.

So, although this sounds very complicated, there are two lines that are repeated four times each – so that’s eight lines dealt with, then there are eleven unique lines – one in the first stanza, then two in each of the subsequent stanzas.

A good example of this poem is ‘Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night’ by Dylan Thomas, which you can easily find if you search for it online.

Haiku: Is a non-rhyming, three line poem, where first and last lines have five syllables, and the middle has seven syllables. It is an Anglicized version of a traditional Japanese form and the subject is often nature or the seasons and the third line is a ‘cutting line’ that juxtaposes (contrasts with) the previous two.

These are two examples of my own Haiku:

Kitchen in silence

Only dishes scream loudly

The eating is done

Puberty looms in

The spring between seasons where

Tributaries swell.

Triolet: For a short poem, a Triolet has an awful lot of rules! It is a bit like a short Villanelle.

It has eight lines in two stanzas of four lines each but, only five lines that are different. Line one is repeated as lines four and seven. Line two is also the last line. The rhyming pattern is A1BaA1 abA1B1, where the capital letters are the repeating lines. Here’s one of mine, called Tiger:

You tear at my skin with piercing words (A1)

And I bleed just a little for you (B1)

Reassemble myself with the view you preferred (a)

You tear at my skin with piercing words (A1)

And my acid retort is unheard (a)

As I observe my existence undo (b)

You tear at my skin with piercing words (A1)

And I bleed just a little for you (B1)

One way to approach writing a triolet (if you fancy it), is to write the last line first, because this is the line that holds the IMPACT of the poem. Then write the line that goes before it and you’ll only have three unique lines left to write.

Free verse: has no rules. You can do what you want with it. Here’s one of mine, called The Awful Dilemma of Parenting:

A decision is made, or made for you, or made without your knowledge

But somehow, anyhow, your child is here, NOW, waiting for guidance

And whether you stumbled into parenthood or not

Each choice you make from this point forward

Directs the future of your progeny, their progeny

And your genes beyond

A significant slice of humanity, for a hundred years to come

Affected by the quality of your parenting skills.

Suddenly, the gravity of fish-fingers

Weigh concrete on your mind

Rondeau: fifteen lines, octosyllabic (eight syllables per line),

A1ABBA- AABA1 –AABBA1, although I cheated a little; because the repeating line at lines nine and fifteen should only be the first four syllables of line one. I guess that’s what you call poetic licence!

Look up the much-loved Rondeau ‘In Flanders Fields’ by John McCrea. Here is my own example of a Rondeau, called The Harbinger of Glottenham:

The coming of a speeding coach (A1)

A squid-ink-black soundless approach (A)

Hidden hop-pickers bathed in sweat (B)

Ignore the horror’s swift beset (B)

The Castle’s future days approach (A)

The Lady’s envoi braves to broach (A)

So slogs his legs up Glotte’nham’s slope (A)

To tell his mistress he regrets (B)

The coming of the speeding coach (A1)

As sliding planes of time encroach (A)

The Lady paces round her moat (A)

Her ghostly spectre paid her debt (B)

And now another’s time is set (B)

The harbinger who brings no hope (A)

The coming of death’s speeding coach. (A1)

Poetic Forms exercise

Choose a poetic form from above, or search for ‘poetic forms’ online and choose one to write your own poem.

I know a lot of poets HATE writing under such restrictions, BUT I really recommend you have a go, because writing to a strict set of rules actually forces you to think more creatively in order to find the right words to tell your story or voice your message.

Poetic clichés

A phrase or opinion that is overused and betrays a lack of original thought.

It is very easy to use clichés in poetry, such as ‘as soft as a feather’, ‘only time will tell’, ‘fall head over heels’ and so on. Finding original ways to describe things can be tricky, but there are techniques to get yourself out of the poetic rut.

Try the exercise below to come up with some unusual phrase combinations.

Note: When I do this exercise with kids’ groups, I get the children to lie on the ground outside, to get a different perspective on the world.

Poetic clichés exercise

This is best done outside, but it could be done inside, or even by looking online.

Nouns: find and list five objects, big or small, singular or plural (preferably a mix of both). Complete this column first, then complete the next columns.

Verbs: find and list five things that move (a mix of mechanical and organic) and next to each one, write a verb that describes its movement.

Adjectives: listen to the sounds around you and list five them with an adjective that describes each sound.

| Nouns | Verbs: | Adjectives |

Stones Pond Lovers Car Sheep | (traffic lights) change (leaves) flutter (tractor) trundles (dogs) dart (gramophone) spirals | (bird sings) mournfully (airplane flies) noiselessly (trees bend) angrily (church bell rings) ominously (bee buzzes) industriously |

Now try out some of the noun-verb-adjective phrase combinations and see if you can find any that could work in a poem. In my example, I liked ‘sheep trundle mournfully’, ‘lovers change angrily’, ‘stones spiral ominously’, ‘cars dart industriously and ‘pond spirals noiselessly’. You can add or remove ‘s’ on the end of words where necessary.

Colour clichés exercise

We often use colour in our writing, both in poetry and prose and it is one area where a bit of imagination can really ‘lift’ your writing and avoid more dreaded clichés.

Take the list of colours below and add more of your own, then go onto the internet and search through images in that colour (Google ‘things that are yellow’ under IMAGES), listing the most unusual or obscure ones you can find.

| Colour | Clichés | Alternatives |

| Yellow | Daffodil, sunset | Cheese, rain hat, submarine |

| Blue | Lake, sky | Cheese vein, corpse lips |

| Green | Grass | Thallium flame, party, coriander |

| Orange | Tango (the drink) | Muppets, fish batter |

| Turquoise | Trolpical sea | Bread mould, Cornish pottery |

| Black | Squid ink, night sky | Top hat, 7 inch (or 12 inch) record |

Try out some of your colour descriptions in your poetry, or prose.

Some sentence examples using my colour alternatives from above:

Her eyes were the colour of Cornish pottery and her hair a Muppet orange.

The Northern Lights turned the sky into thallium flames.

The sea spun around them, shining black as 12 inch record.

I would love to see your poems, please do post them in the comments below or on the YOUR Poetry page.