WHAT DOES DIALOGUE DO FOR A STORY?

Dialogue (or speech) has many important functions within a story.

Look back at any book you have read and ask of any piece of dialogue, “How did that help progress the story, or my understanding of the characters?”

- Dialogue adds ‘voice’ to a story

- Breaks up the monotony of the author’s voice

- Can be used to move a story along

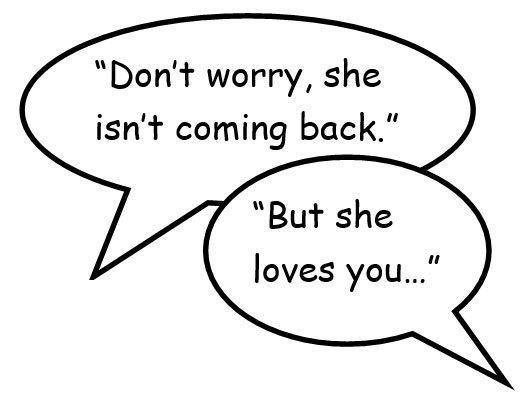

- Can show different points of view about a situation

- Allows the author to reveal more information about the characters

CONVERSATION GENRES

Authors are by nature, extremely interested in other people’s conversations (to put it bluntly – we are nosey). When you listen in on conversations, especially in a coffee shop, pub, the school gate, etc.… you begin to realise that conversations have their own distinct genres (categories/types).

Here are some of my own silly suggestions for the conversation genres you are likely to hear, and I am sure you could think of a few more:

- Banal coffee-shop banter

- School-gate gossip

- Furtive-teenage whisperings

- Frantic-family yelling

- Couple-jousting

- Relationship-breakdown shouting

- Life and death level despair

- Angry strangers arguing

- One-sided romancing

- Romantic-duelling

- Steamy blush-inducing

- Old-time innuendo

- Information sharing

- Situation-controlling

- Evil/mal intent coercion

- Dastardly plotting

LISTEN AND TAKE NOTES

Make a point of listening to the conversations going on around you and note the differences in the way people speak.

Make sure you listen to different age groups to get a feel for how differently they use language – particularly teenagers, who can sound like they are speaking in code.

If you choose to write about teens, be aware that their slang-words and aspects of their language change more often than their socks and getting it wrong in your story can completely alienate them and invalidate your story, so – as with accents, use teen-speak sparingly.

Make notes about:

- Use of language – is it formal, casual or colloquial (everyday)?

- The speed at which different people speak

- What words are frequently repeated, and by whom?

- How do different (foreign and regional) accents make English words sound?

- Some people have unusual intonations or pitch uses (the highs and lows of sentences) – listen to where they occur in their sentences.

- Pay particular attention to the start of conversations, before the ‘meaty’ bit. Are there a random thoughts, half-sentences, niceties (how are you, you’re looking well, nice weather, etc…).

Conversation genre exercise

Write a short conversation between two characters (they can be made up or based on people you have listened to) using one of the ‘fun conversation genres’ above. Try to give each character a consistent and authentic voice – in other words, use the sort of words and phrasing that character would use.

QUICK DIALOGUE FORMATTING RECAP

I have called this a recap because you probably already covered this in school, although some of the rules have relaxed a little as we become more ‘Americanised’ and publishers will have preferences which may differ from your usual use, depending on the audience and ‘house style’.

UK versus USA

Should you use single or double speech (or quote) marks for speech?

Well, it depends on which country you are writing in or for, and yours or your publisher’s preferences. The main thing is to be consistent. If you use double quotes for direct speech (dialogue), you should then use single quotes for indirect speech (quotes). See what popular books in the genre you want to write in use.

- Use speech marks around the words each character speaks.

“I’m going to the match,” Juliette said.

(NOTE: The underlined text ‘he/she/they said’ is often referred to as the ‘dialogue tag’)

- Begin a new paragraph each time a different person speaks – this makes it clear to the reader when the speaker has changed.

“I hate football,” said Emily.

“Really? I can’t understand why,” said James.

“It’s a bunch of men kicking a bag of wind.”

“It’s more exciting than shopping.”

- When breaking a sentence with a dialogue tag, if the second part of dialogue is a continuation of the first sentence, use a comma after the dialogue tag and do not capitalize the first letter of the second piece of dialogue.

“I can’t help it,” Jack said, “it’s just the way I am.”

But if it is a new sentence (by the same person), use a full-stop after the dialogue tag and start the second sentence with a capital letter.

“I don’t know,” Jack said. “By the way, how is your sister doing?”

- Dialogue should end with a full-stop (inside the speech marks) if it is the end of the line, or a comma if a dialogue tag follows.

“That could be fun,” said Frank.Jack shouted, “For goodness sake, do be quiet.”

- When dialogue ends in a question or exclamation mark, dialogue tags that follow still start in lower case.

“What’s new?” she asked.

- If the dialogue ends with an ellipsis (…), you don’t need to add any other punctuation.

“If that’s what you really want…” her voice faltering.

- If your character quotes someone else, then use single quotation marks. (Or vice-versa if using single quotes for the dialogue.)

“But my mum specifically said, I must be ‘IN THE HOUSE’ by midnight, so I have to leave NOW.”

WRITING GOOD DIALOGUE

Avoid making characters tell each other things they already know.

The example below will sound unrealistic and forced:

“How long have we been married, Janet?”

“Well, we got married in Toronto in 2010, so that’s almost ten years.”

You don’t want the reader to know that you are using the dialogue to impart information, so you need to make the information-dumping more sneaky and less ‘in your face’. For example, the important information you need your reader to know is that they married in Toronto, ten years ago, so make something of it and make sure it sounds authentic, so the reader doesn’t feel like they are being ‘informed’.

“Ken and Helen are going to Toronto for their honeymoon – I think they’re staying in that awful hotel next to the one we got married in.”

“Did you tell them it was a dump?”

“I didn’t have the heart – besides, that was over ten years ago, hopefully it’s improved.”

Dialogue exercise 1

Two couples; Gita and Sunil, Arthur and Suzanne, are at a party together. Gita is a police officer and her husband writes crime thrillers, whilst working part-time as a solicitor. They have recently adopted Gita’s twin nieces after her sister passed away. Arthur is an architect and he has two grown up children. Arthur and Suzanne are expecting their first child together and live part-time in France.

The reader does not yet know any of the above information.

Write a short conversation between the characters to give the reader an insight into them.

You don’t need to give all the information and you can include other characters. Do remember to SHOW not TELL.

Don’t enter a scene at the start of a conversation.

Enter a conversation as late as you can because in written dialogue, you don’t need the ‘niceties’ of normal conversation:

“Hi Jess, how are you?”

“I’m good Sue, how are the kids?”

“Oh, you know, it’s all go in our house – did you ever get that patio finished?”

“Not yet, we had a bit of an issue with it.”

“Oh, what was that?”

“Well, we dug up a set of human bones – they’re investigating them.”

The reader wants to get straight to the ‘meat’ of the conversation:

Sue placed her coffee on the slightly sticky table, put her hands to her temples and took a deep breath.

“Oh Jess, it’s been horrible – Dave dug up the old patio and found remains.”

“Human remains?”

“The police think so – they’ve taken over our entire garden.”

It might feel like you are missing out vital parts of normal conversation – and you are, but think of it like this…. if you were listening in on a conversation (perhaps your parent’s, when you were a child) at what point would your ears ‘prick up’ and start to take notice? That is the part your written dialogue should start at, so that you get your reader’s attention and don’t bore them.

Dialogue exercise 2

Melanie bumps into a friend at the supermarket she hasn’t seen for many years. Melanie married a billionaire, who has just been jailed on suspicion of serious fraud.

The reader does not yet know any of the above information.

Write a short conversation between the two characters. Remember to dive straight into the interesting part of the conversation. You can write an opening paragraph to describe them meeting again for the first time and then get straight to the point.

Use ‘Action Beats’ to enrich your dialogue.

Action Beats are the short descriptions of action before, between or after dialogue. They can minimise or even negate the need for dialogue tags, whilst still making it clear who is speaking and also giving a sense of the characters’ emotional state and the setting:

Alex steadied herself, placing a hand softly on Sam’s cheek, “They’ve found her.”

“And…?”

“She’s alive – just.”

“Oh, thank God.” Sam collapsed into Alex’s arms.

Using action beats instead of dialogue tags can also increase the pace of your dialogue, creating a sense of urgency, tension, or even panic.

Dialogue exercise 3

Beatrice has been kidnapped, Tom is speaking to the police officer.

Write the conversation between Tom and the Police officer as he explains what has happened to his daughter.

Use action beats to minimise your use of dialogue tags, to show the pace and urgency of the conversation and describe the emotional state of Tom and how the police officer reacts to him.

Keep your dialogue tags simple.

‘She said’ or ‘he said’ is often perfectly adequate for denoting dialogue. Too many adverbs in dialogue tags (for example, nervously, dejectedly, mournfully) can distract from the actual speech. Instead, to infer how the words are spoken, you can use a character’s actions to demonstrate their mood and emotion to the reader.

Rather than stating how the words are said:

“It’s alright now,” she whispered softly.

You could infer the tone through her actions:

Sally bent down and tenderly pushed a stray hair from the child’s ear, “It’s alright now,” she said.

That’s not to say you should not use different verbs and adverbs, such as ‘she shrieked’, ‘he admonished’, ‘they wailed helplessly’, etc… just don’t over-use them – less is more powerful.

Dialogue exercise 4

Replace ‘she wailed dejectedly’ in the dialogue below with ‘she said’ and add a sentence to describe your character’s mood, action or feelings to show the reader how Felicity says her dialogue instead.

“I couldn’t reach him,” she wailed dejectedly.

Or create your own piece of dialogue with actions, instead of adverbs to denote how the words are delivered.

Use dialogue to reveal information about your characters.

You might need to tell your reader certain bits of information about your character’s personality or characteristics – things that are necessary to the story, or to the reader’s understanding of the character and their actions but, long sections of narrative can be off-putting and dull. A more interesting way to tell your reader about your character is to reveal that information through conversation.

For example, instead of telling your reader a character has had a limited education, you could make this clear through the things he says:

“Do you want the spaghetti carbonara or the burger?” asked Joe.

“I don’t eat nothing I can’t spell,” said Jack.

What can you tell about Maria’s life and how does Jean feel about it?

“How can you stand to watch that tv show? It’s so not like that!” Maria admonished.

“Because some of us haven’t ever lived the Californian dream,” hissed Jean.

The family below are probably struggling for money, but resourceful.

“Mum, you need to fix the zipper again, and the inside of the pocket has another hole.”

“Pop it on the side,” said Martha, “I’ve got your dad’s best socks to darn first.”

Dialogue exercise 5

Write conversations between Emily and any other characters you wish to add in the situation detailed below. The dialogue should reveal that Emily is medically trained, but currently unemployed.

Emily is in the same shop as Georgia, but does not know her. She sees Georgia become unwell.

Continue the story from the following sentence:

Georgia slumped against the shop counter, her legs went weak and she felt herself begin to fall…

Always try to speak your dialogue aloud.

Test your dialogue – if it is ‘clunky’, it will not flow and you will find it difficult to get the sentences out, or it might be repetitive, or worse still – boring.

If you have a willing friend (or friendly writing group), ask them to read your dialogue so that you can listen to it. This is important, because dialogue sounds entirely different when read aloud, than it does in your head.

A QUICK NOTE ABOUT AUTHENTIC ACCENTS

Language is important for portraying regional and foreign accents. It can also denote age, social group, education, situation and mood, but when writing an accent, just use the bare minimum – less is most definitely more, or it will become too difficult to read.

I would love to see what you do with the exercise, please do feel free to post them in the comments below.